GALLERY OF MACHINES

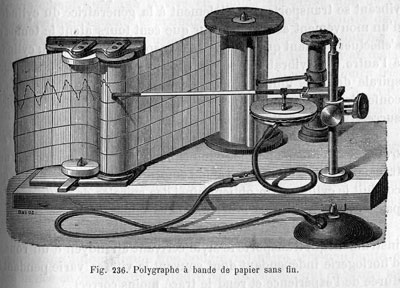

In the second half of the nineteenth century, European scientists like Etienne-Jules Marey, created polygraphs like this one to record the bodily responses of subjects while they experienced mental processes, such as reaction times and fear.

In 1921, Larson rigged a device to continuously record the blood pressure and breathing depth of subjects while they answered “yes” or “no” to alternating relevant and irrelevant questions. And he soon found the ideal experimental set-up to prove his technique: a theft in a college sorority. The first of these, the College Hall case, showed how the lie detector might be used to extract a confession. Here, Larson (left) and Vollmer test a Berkeley undergraduate on his first machine, currently held by the Smithsonian Institution.

Keeler first began working to create his Keeler Polygraph in 1923 while assisting August Vollmer clean up crime and police corruption in Los Angeles, where Vollmer was serving as temporary chief of police. Keeler continued to experiment with designs while an undergraduate at Stanford University. In 1929 he signed a production agreement with the Western Electro-Mechanical Corporation of Oakland, California, and after much haggling was granted a patent on January 31, 1931, for his “Apparatus for Recording Arterial Blood Pressure,” Patent No. 1,788,434, The Keeler Polygraph pictured here is held by the Smithsonian Institution.

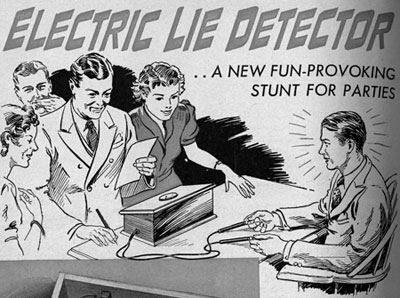

One alternative design of lie detector focused on galvanic skin resistance, which is generally a proxy for sweatiness. Simple versions of such devices can be made at little expense, as suggested by this Popular Science Monthly article of April 1940. In fact, most polygraphers found this measure to be too volatile for good results, though Keeler added it to his polygraph in 1939 when he switched his manufacturer to Associated Research of Chicago.

|